Progression of ADPKD

This information is for people with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), their families and friends. It explains how the disease reduces kidney health over a person’s lifetime. This is known as ‘progression’.

If you have ADPKD, your kidney function is likely to begin to fall in your 30s or 40s. If you’re younger, you might still find this factsheet useful in helping you to know what to expect later in life.

Contents

- What do healthy kidneys do?

- What happens as ADPKD progresses?

- How might I feel about my disease progression?

- Will I develop kidney failure, and when?

- What is chronic kidney disease

- What are the symptoms of poor kidney function

- What other problems can ADPKD cause as it progresses?

- How often will my kidneys be checked?

- How is reduced kidney function treated?

- How can I protect my kidneys from damage?

- More information from the PKD Charity

- Authors and contributors

What do healthy kidneys do?

Before looking at ADPKD progression, here’s a quick reminder of what healthy kidneys do for the body:

- filter your blood to remove waste and extra fluid

- balance levels of salts, minerals and acids in your blood

- help to control your blood pressure

- tell your body when it needs to make more red blood cells

- activate vitamin D to help keep your muscles and bones healthy

What happens as ADPKD progresses?

If you have ADPKD, the size and number of kidney cysts you have will gradually increase over the years. This will make your kidneys grow bigger. The cysts will start to damage some of your healthy kidney tissue, which has less room.

While a normal kidney is about the size of a potato, the kidneys of people with ADPKD can become as large as a rugby ball. This is because of the large cysts within them.

Figure 1: Drawing of the inside of a polycystic kidney (right), showing cysts of different sizes, compared with a normal kidney (left).

Although damaged tissue can’t filter as much blood as normal, the healthy parts of your kidney will make up the work for many years.

At some point, there won’t be enough healthy tissue to do all the work your kidneys are meant to do. This is known as chronic kidney disease (CKD). Until your kidney function gets very low, you probably won’t have many symptoms.

If you get symptoms of poor kidney function, you may need to change your diet and take medications to help. We explain this later.

Many but not all people with ADPKD eventually get kidney failure. At this point, the kidneys are not doing the basic amount of work your body needs. This will make you unwell. If you get kidney failure, kidney replacement therapy — which can be dialysis or a kidney transplant — can replace some of the work of your kidneys and prolong your life.

You can choose not to have dialysis or a transplant if you prefer. It’s important to understand your life could be much shorter without these treatments. Most people who make this choice are in old age and have additional health problems.

How might I feel about my disease progressing

Some people with ADPKD find that not knowing when their kidney function will decline makes them anxious.

Other challenging or stressful times include:

- finding out that your kidney function has got worse

- waiting for a donor kidney to become available for transplant

However, with regular kidney check-ups, you should know well in advance that your kidney health is decreasing and be able to start planning with your doctor.

As time goes on, many people with ADPKD say they better adapt to living with the condition and feel more positive.

Some people with ADPKD find their enlarged abdomen affects their body image or self-esteem. ADPKD can also affect relationships and sex life.

If ADPKD is affecting your emotions, mental health, body image, self-esteem or sex life, chat to your doctor about what support is available.

For more information and support, see living well with ADPKD and support.

Will I develop kidney failure, and when?

Understandably, many people with ADPKD worry about if and when they’ll develop CKD and kidney failure.

Not everyone gets kidney failure and so not everyone needs dialysis or a transplant. The age that kidney failure happens can vary from person to person (and even within the same family).

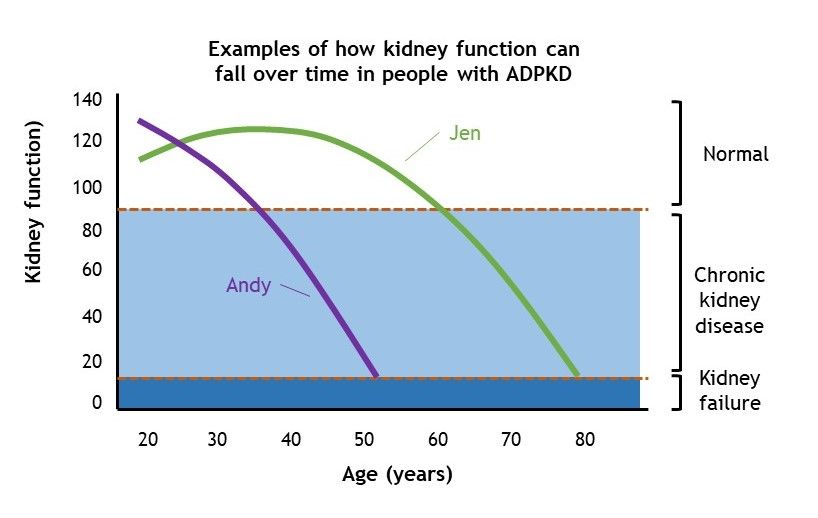

We show this in the graph below. Andy will need to have dialysis or a transplant about age 50, while this happens in Jen’s late 70s.

Figure 2: Two examples of how ADPKD can progress over a person’s lifetime.

About half of all people with ADPKD get kidney failure by the time they turn 60. Yet, a quarter of people with ADPKD reach age 70 without their kidneys failing.

You’re more likely to have slowly progressing ADPKD if:

- you have a PKD2 gene alteration (rather than PKD1 gene alteration)

- you’re female (female hormones might protect the kidneys a little)

- your kidneys are not too enlarged

Your doctor can’t predict for sure if and when you’ll get kidney failure. However, they can track your kidney function in check-ups using urine and blood tests. Checking the size of your kidneys using scans might help to predict progression too. These predictions can be wrong for some people.

If anxiety about your kidney function is affecting your life, ask your GP or kidney specialist to refer you for support.

Tests to monitor ADPKD progression

Measuring kidney function

Kidney function is usually measured by estimating how much blood your kidneys can filter in a minute. This is known as the estimated glomerular filtration rate, or eGFR [KRUK Tests]. eGFR is measured in millilitres of blood filtered in 1 minute per 1.73 m2 of your body size [KRUK Tests]. This is written as ml/min/1.73 m2.

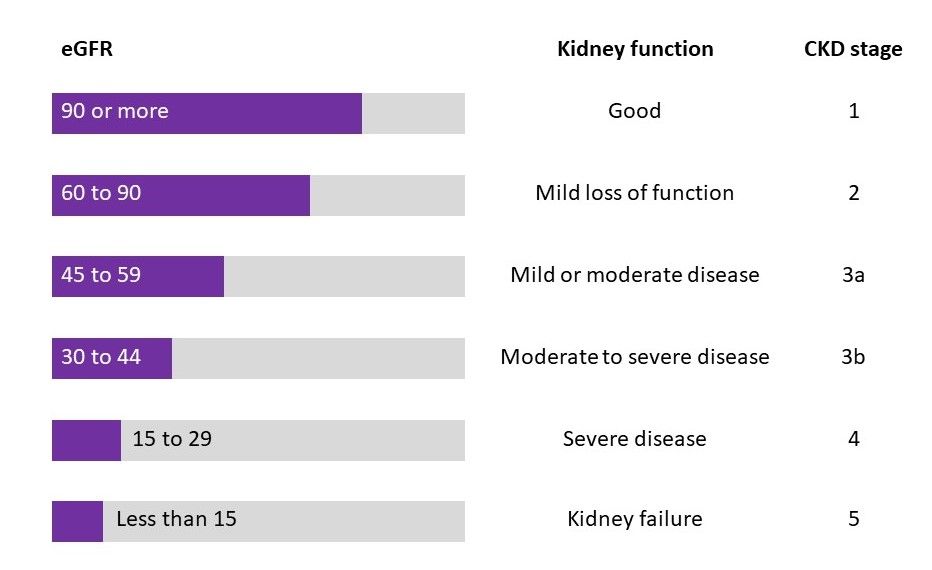

Your eGFR gives a rough idea of how well your kidneys are working (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Understanding what your eGFR result means.

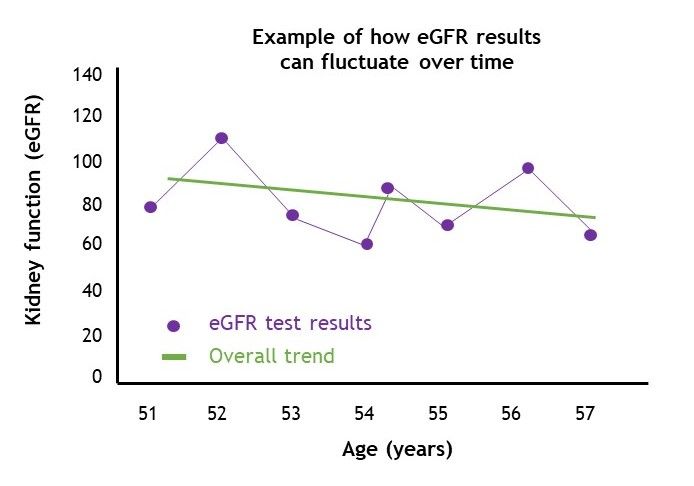

It’s important to understand that eGFR is only an estimate and the results can waver, especially if your kidney function is quite good. The test results can be affected by many things, such as time of day, your diet, medications, hard exercise and the methods the hospital lab uses. Don’t read too much into one unusual reading before talking with your kidney specialist.

If your eGFR result is much lower than usual, your kidney specialist will repeat the test a few times. This is to work out if your kidney function is truly dropping or if the estimate was low.

When monitoring your kidney health, your kidney specialist will be looking at the overall trend over a few years.

Here is an example of how eGFR readings can waver over time, and the overall trend your doctor will be looking for:

Figure 4: Example of how eGFR can waver over time.

Checking for kidney damage

A simple urine test called an albumin:creatinine ratio, or ACR, can check for signs that your kidneys are damaged. This test looks to see whether there is a protein called albumin in your urine. Having more albumin than usual in your urine is a sign of kidney damage. An ACR of 3 mg/mmol or lower suggests mild damage, while an ACR of 30 mg/mmol or higher suggests severe damage.

Measuring kidney size

Your doctor will estimate the size of your kidneys when you’re diagnosed with ADPKD. This is done using imaging scans and is called ‘total kidney volume’, or TKV.

Healthy men have a total kidney volume of roughly 300–430 ml while for women it is 220–330 ml. As ADPKD progresses, your kidneys become larger as the cysts within them grow.

On average, the kidneys of a person with ADPKD will grow by 5% or 6% each year. For example, if a person’s total kidney volume is 1000 ml this year, it may be 1060 ml next year.

The amount the kidneys grow each year differs from person to person.

Because blood tests can check kidney health, some experts recommend that people with ADPKD don’t need regular scans to estimate TKV, unless they have symptoms.

Scans to estimate your TKV can be useful to see whether a treatment for ADPKD called tolvaptan (brand name Jinarc®) is suitable for you. TKV might also be used to see whether a clinical trial is an option for you.

What is chronic kidney disease?

If your kidneys show signs of ongoing damage or a drop in function, you will be diagnosed with ‘chronic kidney disease’ (CKD). ‘Chronic’ means the disease continues for 3 months or more. However, a chronic disease is not always serious.

CKD can be mild, moderate, or severe. It depends on your kidney function (your eGFR) and signs of kidney damage (your ACR). We explained these tests earlier.

Having mild CKD (stage 2) means your kidneys are functioning quite well but may show some damage. If your CKD is moderate or severe (stage 3 or 4), this means your kidney function is reduced quite a lot and your kidneys are damaged. The most serious stage of CKD is stage 5, which is also called ‘end stage kidney disease’. At this stage, your kidneys are failing. Dialysis or a kidney transplant to replace their function and prolong your life.

What are the symptoms of poor kidney function?

If you have mild or moderate CKD, you probably won’t have symptoms associated with reduced kidney function. If your CKD worsens, you’re likely to start feeling less well.

People with severe CKD or kidney failure are especially likely to get:

- tiredness and lack of energy

- dry skin

- difficulty sleeping

- feeling sick

- poor appetite, which may cause weight loss

- less interest in sex, and finding it harder to get sexually aroused

- bone or joint pain

- muscle cramps, itchiness and restless legs

- swollen ankles, feet or hands (due to fluid retention)

- feeling dizzy or light-headed

- finding it hard to concentrate

- feeling sad, irritable or anxious

- headaches

- shortness of breath

What other problems can ADPKD cause as it progresses?

As your kidney cysts grow, you’re more likely to get other problems linked to ADPKD. These include:

How often will my kidneys be checked?

You should have a kidney check-up at least once a year. How often you have check-ups will depend on how much ADPKD is affecting your kidneys and your preference. People with poorer kidney function usually see their kidney specialist more often than those with better kidney function.

If your kidney function is currently good, you’ll probably only need a check-up once a year. If you have severe CKD, you’re likely to have a check-up every few months.

How is reduced kidney function treated?

If you have mild or moderate CKD, you may not need any treatment. There are some things you can do to keep healthy, which we explain in the next section.

If your kidney function drops further and you start getting symptoms, you may need to:

- make changes to your diet

- follow your doctor’s advice about the amount of liquid you drink

- take medicines to help keep you healthy

If doctors think your kidneys will fail in the next year or two, they’ll chat to you about your preferences for dialysis, a transplant or neither.

How can I protect my kidneys from damage?

There’s no cure for ADPKD. You can slow the progression of your ADPKD and protect your kidneys by taking these 3 steps:

- Follow your doctor’s advice to control your blood pressure if it’s high.

- Follow our tips on diet and lifestyle.

- Avoid medicines that may harm your kidneys.

If you have mild to moderate CKD and your ADPKD is progressing rapidly, you may be eligible for a treatment called tolvaptan (Jinarc®). In trials, tolvaptan slowed the speed at which some people’s kidneys grew and also slowed their kidney damage.

You can find out more about tolvaptan in our fact sheet on treatments for ADPKD.

More information from the PKD Charity

Authors and contributors

Written by Hannah Bridges, PhD, Independent Medical Writer at HB Health Comms Limited. Reviewed by Dr Matthew Gittus, Academic Clinical Fellow, Renal Medicine, Northern General Hospital, Sheffield.

With thanks to all those affected by ADPKD who contributed to this publication.

Ref No: ADPKD.P.v2.0

Last updated: July 2023

Next scheduled review: July 2025

Disclaimer: This information is primarily for people in the UK. We have made every effort to ensure that the information we provide is correct and up to date. However, it is not a substitute for professional medical advice or a medical examination. We do not promote or recommend any treatment. We do not accept liability for any errors or omissions. Medical information, the law and government regulations change rapidly, so always consult your GP, pharmacist or other medical professional if you have any concerns or before starting any new treatment.

We welcome feedback on all our health information. If you would like to give feedback about this information, please email

If you don't have access to a printer and would like a printed version of this information sheet, or any other PKD Charity information, call the PKD Charity Helpline on 0300 111 1234 (weekdays, 9am-5pm) or email

The PKD Charity Helpline offers confidential support and information to anyone affected by PKD, including family, friends, carers, newly diagnosed or those who have lived with the condition for many years.