This fact sheet is for people with ADPKD and their family and friends. It explains the gene alterations that can cause ADPKD, how they’re inherited, and how genetic testing works. If you’re wondering whether you’re eligible and whether to go ahead with testing, you’ll find useful information here.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is inherited. This means it can be passed on from a parent with ADPKD to their child through their genes. Genes are the instructions the cells in our bodies need to grow, divide, and do their jobs.

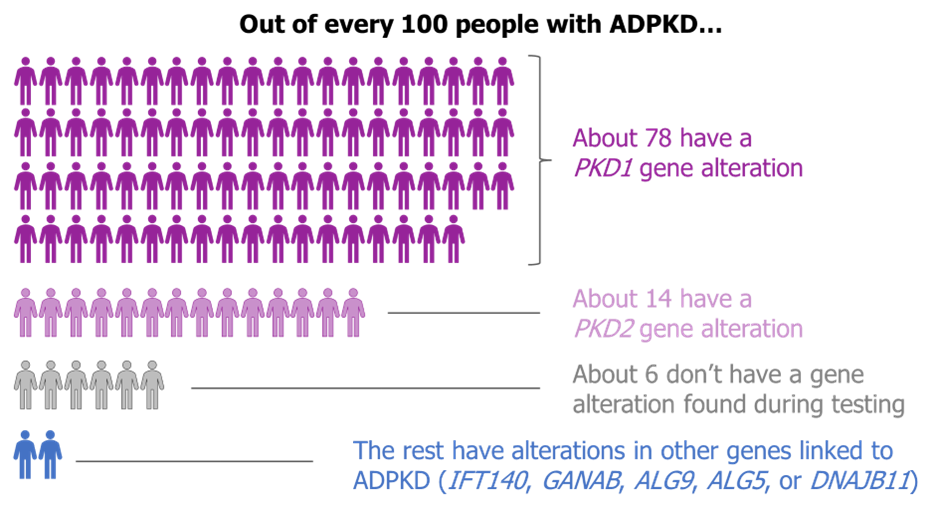

There are many different alterations (mutations) that can occur in genes linked to ADPKD. Usually, ADPKD is caused by an alteration in either the PKD1 or PKD2 gene. There are also rarer gene alterations that can cause ADPKD (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Genetic alterations in ADPKD

A genetic test can look for gene alterations that cause particular health conditions. It is usually done on a blood or saliva sample.

Genes are made of DNA — a long chain of molecules linked together to form a code. This code acts like a recipe, telling the cell how to make a particular protein.

In a genetics laboratory, a scientist will use a special machine called a sequencer to read the DNA code of your genes. The code can then be studied to look for alterations linked to kidney diseases that cause cysts, including ADPKD. These gene alterations are sometimes referred to as ‘pathogenic’ or ‘likely pathogenic’ mutations, because they cause disease.

If a gene alteration is found that is responsible for your ADPKD, samples of DNA from family members can be checked for the same alteration. Relatives who have the same gene alteration will develop ADPKD too, even if they don’t have symptoms yet.

Tests for alterations in genes that can cause ADPKD are typically only available to people who either have or are suspected to have this condition. ADPKD is not a common disease and people without symptoms or a family history are unlikely to have it or benefit from testing.

Often, adults with ADPKD can be diagnosed based on an ultrasound of their abdomen (tummy) to look for cysts in their kidneys and liver.

Examples of when a genetic test for ADPKD might be used are:

Your kidney specialist will be able to explain whether you’re eligible for a genetic test and arrange this test for you. You may also be asked to have genetic counselling to help you understand the pros and cons of testing before going ahead.

If you’re having a genetic test for ADPKD and no one in your family has been tested before, the results should be available within 18 weeks (about 4 months).

However, results may take longer to come through as the NHS recovers from the pandemic. If an ADPKD gene alteration has already been found in a relative, your test result might come through within weeks. This is because the laboratory staff already know which gene alteration they’re looking for.

If you have ADPKD and have genetic testing, there is over a 9 in 10 chance that the laboratory will find the gene alteration causing your condition.

The possible results of the test are:

In England, genetic testing for ADPKD is currently carried out using whole genome sequencing. This means your entire genetic code is read but only the genes associated with kidney cysts are fully analysed.

You may be asked whether your whole genome sequence can be stored in the National Genomic Research Library. This is so your data can be used anonymously (without your name) in studies aiming to improve the diagnose and treatment of diseases in the future. Your genetic counsellor can explain what this means for you.

If you’re not eligible for genetic testing on the NHS, ask your doctor to explain why. It might be that you’re not at risk of having ADPKD, or the results would not alter your care plan.

Some companies offer private genetic testing, which you pay for yourself or via health insurance. Before using a private company, ask about the expertise of the laboratory as well as the doctor interpreting the results. This is because genetic tests are highly technical, and the results can be hard to understand.

The gene alteration you have might give some clues as to how your ADPKD may progress, but specialists won’t be able to predict exactly when your ADPKD will worsen. This is because factors other than genes affect ADPKD too.

Relatives with the same gene alteration can get different symptoms or experience problems at different ages.

On average, compared with people with PKD1 gene alterations, those with PKD2 gene alterations tend to have ADPKD that is:

Alterations in other genes linked to ADPKD are uncommon, and we’re still learning about them. Some seem to cause ADPKD that is less severe and has symptoms starting later in life than ADPKD caused by PKD1 or PKD2.

It can be difficult to decide whether to have genetic testing. It may help to talk to a genetic counsellor or someone with experience of testing for ADPKD, as well as friends and family.

Below are some of the pros and cons. Your doctor can refer you to a genetic counsellor to chat these through.

Genetic counselling is not the same as psychological counselling. Sessions may be run by a genetic counsellor, a clinical geneticist or a kidney specialist. They’ll give you information to help you decide whether or not you want to have a genetic test. You’ll talk through the pros and cons, your views, and what’s most important to you.

After genetic counselling, you’ll choose whether you want to go ahead with the test. You don’t have to make an immediate decision.

Having genetic testing can sometimes affect insurance related to your health (such as life insurance, health insurance, or critical illness cover). This depends on the circumstances of the test:

The Genetic Alliance has further information on insurance for people with a family history of an inherited disease and those considering having a genetic test.

Most people with a PKD1 or PKD2 gene alteration inherited it from a parent with ADPKD. Less commonly, the gene alteration can happen by chance early in life (when a person is an embryo).

If you have a PKD1 or PKD2 gene alteration, there is a 1 in 2 chance (50% chance) of passing it on to each child you have.

We show this in the diagram below (Figure 2). Each person has two copies of a PKD gene. Here we show one parent with two normal genes (green), and one parent with one normal (green) and one altered gene (purple). The second parent has ADPKD.

The child will inherit one gene from each parent. So, in the scenario on the left, the child inherits the altered gene (purple) from the affected parent, and a normal gene from the other parent. This child will have ADPKD.

In the scenario on the right, the child inherits a normal gene (green) from each parent and will not have ADPKD.

Figure 2: ADPKD inheritance

The PKD1 and PKD2 genes are codes for making two proteins called polycystin 1 and polycystin 2. These proteins are found on the surface of cells lining the kidney tubules that are involved in making urine.

People with a PKD1 or PKD2 gene alteration have different versions of polycystin 1 or polycystin 2. The changes to the proteins make it more likely that cysts will grow in the kidney.

The precise function of polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 is currently unclear. Researchers are looking into how the cells lining kidney cysts differ from healthy kidney cells to help in the design of potential new treatments.

Most children with ADPKD don’t have symptoms that cause problems. The only way to know whether a child has ADPKD is using an ultrasound scan of the kidneys or genetic test.

Children at risk of having ADPKD can have genetic testing at any age. If you’re considering getting your children tested, ask to be referred to a genetic counsellor. They can explain the pros and cons.

If you decide against genetic testing for your child for the time being, you can ask for an ultrasound scan instead if you like. Your doctor will also recommend that your child has blood pressure check-ups from age 5 years onwards. This is because ADPKD can cause high blood pressure in children as well as adults, and it’s important this is treated.

If you or your partner have ADPKD, there is a 1 in 2 (50%) chance your child will inherit ADPKD. This risk applies to each child you have.

Very occasionally, a routine ultrasound scan during pregnancy will show a baby has cysts in their kidneys due to ADPKD.

If you or your partner have a gene alteration causing ADPKD, you can have your baby tested before birth if you want to. This typically involves taking small samples of amniotic fluid or placenta (called a chorionic villus sample or CVS), together with ultrasound scans. Amniotic fluid is the liquid that surrounds the baby in the womb, while the placenta provides oxygen and nutrients to the baby.

It’s best to discuss options before becoming pregnant: ask your doctor or kidney specialist to refer you to a genetics centre.

If you have ADPKD, a special type of in vitro fertilization (IVF) called pre-implantation genetic testing (PGT) means you can have a child without ADPKD. This procedure is not available to everyone, and not all couples choose to have it.

PGT involves the steps shown in the next diagram (Figure 3). If you get pregnant from PGT, your child won’t have ADPKD. But like any IVF, it doesn’t always lead to pregnancy.

If you want to find out more about PGT for yourself and your partner, ask your GP, genetics clinic or kidney specialist to refer you for a PGT consultation.

PGT is only offered in a few centres. Although ADPKD is one of the conditions approved for PGT, not everyone is eligible to have it on the NHS. Your eligibility depends on your circumstances, the area of the UK you live in, your health, and whether you have other children. For more information see the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority website and Genetic Alliance UK website.

Figure 3: Steps of pre-implantation genetic testing

Written by Hannah Bridges, PhD, HB Health Comms Ltd, UK. Reviewed by Professor Richard Sandford, Academic Department of Medical Genetics, University of Cambridge, UK.

With thanks to all those affected by ADPKD who contributed to this publication.

Ref No: ADPKD.GA.V2.0

Last updated: September 2022

Next scheduled review: September 2024

Disclaimer: This information is primarily for people in the UK. We have made every effort to ensure that the information we provide is correct and up to date. However, it is not a substitute for professional medical advice or a medical examination. We do not promote or recommend any treatment. We do not accept liability for any errors or omissions. Medical information, the law and government regulations change rapidly, so always consult your GP, pharmacist or other medical professional if you have any concerns or before starting any new treatment.

We welcome feedback on all our health information. If you would like to give feedback about this information, please email

If you don't have access to a printer and would like a printed version of this information sheet, or any other PKD Charity information, call the PKD Charity Helpline on 0300 111 1234 (weekdays, 9am-5pm) or email

The PKD Charity Helpline offers confidential support and information to anyone affected by PKD, including family, friends, carers, newly diagnosed or those who have lived with the condition for many years.