Understanding pain in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD)

This is a report of a survey carried out during the ADPKD Information & Support Day, Birmingham Hospital, 23rd January 2016. The issues of pain were explored in a workshop during the day. We are grateful to participants who completed the survey questionnaire.

Published by:

Dr Michael Lee FRCA PhD FFPMRCA

University Lecturer & Honorary Consultant in Pain Medicine

Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge

How common is pain in patients with ADPKD?

Pain is common in patients with ADPKD. Nearly 1 in 10 (7%) patients suffer an episode of severe pain a year. These painful episodes are usually related to infection, stones or bleeding into cysts and subside after treatment. However, about 2 in 3 (60%) patients suffer constant pain, which may be related to enlarged kidney cysts. These cysts can distort the kidney and compress internal organs. Their sheer size can cause abnormal body posture, which may lead to musculoskeletal pain.

Not everyone with large polycystic kidneys experiences chronic pain. Research has shown that the severity of pain does not correlate with kidney size. But it may be that pain depends on where the cysts are within the kidney, rather than the size of the kidney. Or that only cysts over a certain size cause pain. We should also remember that pain is a sensation that is generated by the nervous system. The sensitivity of the nervous system ultimately determines the amount of pain that results from kidney damage.

How do we normally sense pain?

The scientific word for ‘pain nerves’ is nociceptors. ‘Noci’ comes from the Latin nocere, which means to injure. Nociceptors detect damage to the body and send signals up to the brain. The brain then generates the feeling of pain from these nerve signals.

The brain isn’t just a passive receiver of nerve signals. It can amplify or dampen the signals coming up from the nerves. For example, the brain can dampen the nerve signals to decrease pain despite damage to the body to give athletes the winning edge during sports. When the competition is over, the brain switches from dampening to amplifying nerves signals to increase pain, which enforces rest to promote recovery.

What might be happening to the nervous system in chronic pain?

Damage to the body causes nociceptors to fire off strongly. Scientists have discovered that strong and frequent signals from nociceptors increase the sensitivity of the spinal cord, brainstem and the brain to subsequent nerve signals. The increased sensitivity is called central sensitisation because the spinal cord, brainstem and brain comprise the central nervous system. Central sensitisation causes areas surrounding the injured part of the body to feel painful. For example, the stroking the normal skin around or near any knife cut will feel uncomfortable or even painful for up to a few inches away from the cut. This increased discomfort or pain thought to be due to central sensitisation.

Central sensitisation is useful because it causes increased pain and tenderness, which protects the damaged body part. The increased sensitivity should fade away with healing. If that doesn't happen, pain is likely to continue or get worse. That’s what researchers suspect happens in some patients with chronic pain (https://www.painscience.com/articles/central-sensitization.php).

Is central sensitisation relevant to chronic pain in patients with ADPKD?

We don't know whether central sensitisation is relevant to chronic pain in patients with ADPKD. However, we do know that central sensitisation contributes to chronic pain from nerve damage, for example in patients with diabetes or shingles. Pain from nerve damage is called neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain has distinct qualities. Patients with neuropathic pain often use words like 'burning', 'electric shocks', 'tingling', and even 'numbness' to describe what they feel.

Why might we want to know whether pain in ADPKD has neuropathic qualities?

There are drugs for neuropathic pain but they all have side-effects. But they may be worth trying if there's some aspect of pain in an ADPKD patient that is neuropathic.

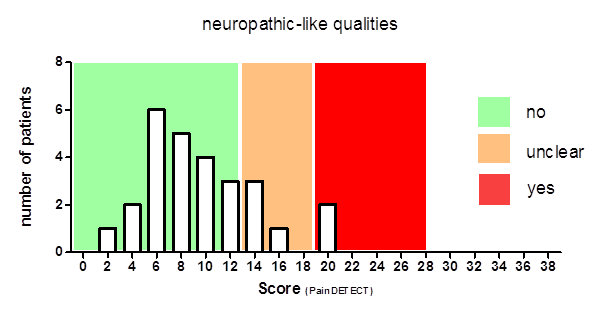

We thought that it'd be interesting to know what words patients with ADPKD use to describe their pain. There are various questionnaires that assess the qualities of pain. One commonly used questionnaire is called PainDETECT. This questionnaire has been used to assess neuropathic qualities of pain in patients with different medical conditions and is simple enough to use as a survey at a ADPKD Information & Support Day.

What are the results of the survey?

There were 34 questionnaires returned. The graph below shows the number of participants for each score. The scores range from 0 to 38. Scores falling into the green zone indicate pain without neuropathic qualities, and those in the red zone indicate pain has neuropathic qualities. Only two patients we surveyed had a definite neuropathic quality to their pain.

What's next?

The pilot survey gives us a glimpse about the nature of pain in patients with ADPKD. What we really want are tests proven in research studies that tell us where the pain is coming from for a particular patient. For example, is pain related to large kidney cysts, or poor posture, or abnormal nerves for that patient? Such knowledge will help tailor treatments for individual patients. Research into 'personalised' treatment for chronic pain is growing steadily, and we hope that the survey highlights the need for pain research in patients with ADPKD specifically.

- Hits: 5451