Find out when kidney transplants may be needed, how they are performed, what it’s like to have this surgery, the risks and benefits, and alternative treatments available. If you’re considering having a transplant, please also talk to your kidney specialist and transplant team for advice and information.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is a genetic condition that causes cysts to grow in the kidneys. As these cysts gradually enlarge, kidney function falls, which results in kidney failure for many people. In the UK, ADPKD affects an estimated 70,000 people, but not everyone with ADPKD will experience kidney failure.

If the kidneys are not filtering the blood properly, excess fluid and toxins collect in the body. This has harmful effects on all systems of the body. If you have kidney failure, you’ll need dialysis or a kidney transplant to survive. Dialysis or a transplant are known as renal replacement therapy and replace some of the work your own kidneys can no longer do.

On average, people with ADPKD start renal replacement therapy aged 55 years, but this differs from person to person. Of all the adults in the UK starting renal replacement therapy, approximately 1 in 14 (7%) have ADPKD.

Kidney transplantation is the best renal replacement for ADPKD patients with kidney failure.

Having a kidney transplant before needing dialysis – known as pre-emptive kidney transplantation – has advantages over having a transplant after starting dialysis. These include: avoiding needing surgery to prepare for dialysis, having a better transplant and a longer survival time. It also reduces costs for the NHS.

In the UK, pre-emptive kidney transplantation is offered when your estimated glomerular filtration rate or eGFR (a measure of your kidney function) has fallen below 15 ml/min.

Martin had a pre-emptive, living kidney donation

“When I dropped below eGFR 20, it was suggested that I start thinking about live transplant. My great niece volunteered and was a really good match. From the time she agreed to donate to transplant was about 2¾ years. I had the transplant at eGFR 9, in October 2016.

The transplant team told me that mine was a ‘textbook’ pre-emptive live donation. My niece sailed through it – she wanted food as soon as she came back from theatre! The transplant was on the Thursday and she went home on the Monday. I was in the full week. Once out, I was very well looked after by my wife.”

Nicki needed a transplant after having her own diseased kidneys removed

“Dialysis hardly worked for me at all. The doctors had said that my need for a transplant was urgent. Around 3 months after an operation to remove my PKD kidneys, the consultant felt I could risk going on the transplant list.

Just one week later, I was at home and I received a call to go immediately to the hospital. I had no reservations about having the transplant even though I realised I was vulnerable to infection and still had pain from recent surgery. My creatinine* went from 1,400 to 100 overnight and I woke up feeling like a brand-new woman. I was well cared for and a future felt possible once again.”

*Creatinine is used to measure kidney function. High levels indicate poor function.

If your kidneys are failing, a kidney specialist and surgeon will thoroughly assess your health and do tests to check whether you’re suitable for the procedure.

Kidney transplantation involves major surgery. Most ADPKD patients with kidney failure are suitable for the procedure. However, people with severe diseases involving the heart, blood vessels or lungs, those with uncontrolled cancer or an active infection, and those with a predicted survival of only a few years aren’t suitable. They’ll be offered dialysis instead.

ADPKD patients are more likely to have an enlarged blood vessel (an aneurysm) in the brain, which can be dangerous, especially during surgery. Before the transplant, ADPKD patients with a family history of aneurysms need investigations for a brain aneurysm with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If an aneurysm is found, it should be treated before the kidney transplant operation.

Kidneys for transplantation can be donated from living or deceased people.

A transplant from a living donor (usually a family member or friend) has several advantages:

If a friend or family member is keen to donate a kidney to you but isn’t a match, it might be possible to arrange for a kidney swap with another family or couple in a similar situation. However, finding a living match is not always possible. About two-thirds (67%) of kidneys donated in the UK are from a deceased donor.

If you need a kidney transplant and don’t have a living donor, you’ll be put on the national waiting list. The average waiting time for a deceased donor kidney transplantation is 3 years. Once on the list, you’ll need to be able to get to the hospital whenever a donor kidney becomes available – this could happen at any time, day or night.

Matching the donor to you is done by testing your blood group and tissue type (using human leucocyte antigens or HLAs).

Stephen found the wait hard, but coped by keeping fit

“There were some dark periods as one is waiting with a real chance of time running out before a kidney becomes available. Nonetheless I was determined to keep fit and look after myself so that I would be able to take the opportunity should the call ever come.”

Rob had some false starts before a suitable kidney was found

“Life is quite normal; until you get the call! My first call was at 1 am. I went to Manchester Royal and had to wait around for about 30 minutes, then was given a bed. I was just in the middle of getting my gown on and a nurse came and said that the kidney wasn’t good enough and I could go home. I arrived home at 3.30 am. A very surreal experience! I had a further 3 calls before I was successful.”

Andy found the wait for a donor kidney and liver a strain

“Being on dialysis was sometimes an emotional strain - and probably on loved ones too. Waiting for a donor with no set date rather than having a live donor planned is just that - a 'waiting game' and can be tortuous. But however hard dialysis could get, I remembered it was keeping me alive.”

Most ADPKD patients don’t need to have their own kidneys removed before their transplant. However, this is sometimes done, for example if the kidneys are causing pain or bleeding, are infected, are taking up too much space in the abdomen, or if kidney cancer is suspected.

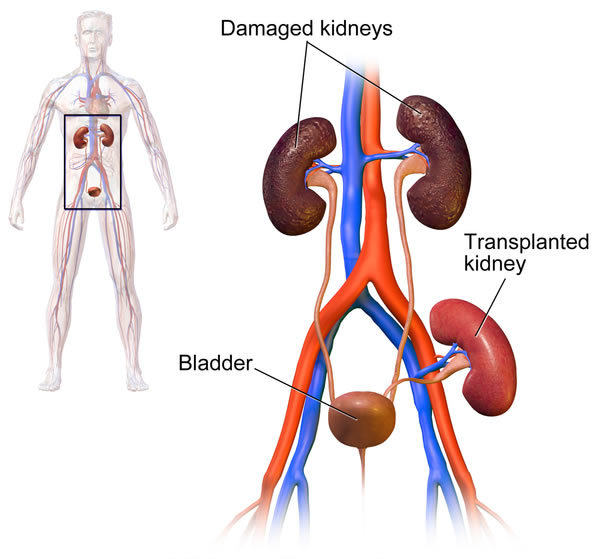

In the transplant operation, your surgeon will place your new kidney in your groin and connect it to your blood vessels and bladder (see Figure 1). This takes about 3 hours.

Most patients recover well after a kidney transplant and can leave hospital after about a week. To prevent your body rejecting your donated kidney, your immune system will need to be dampened down using medication called immunosuppressants. Common immunosuppressants include tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, prednisolone and sirolimus. These should be taken without missing a single dose.

Your transplant team (including surgeon and kidney specialist) will closely monitor the doses of the drugs you’re using to check your immune system is not being too strongly or too weakly suppressed. It’s important to get the balance right. If your immune system is too strongly suppressed you’ll be more likely to get infections (of bacteria, viruses and fungi) and could be at increased risk of developing cancer.

However, if you don’t take enough immunosuppressant medication your body will attack your donated kidney (known as rejection). Rejection of a transplant can be confirmed using a biopsy. Sometimes, rejection can be stopped with stronger immunosuppressants, but if rejection progresses it can lead to early failure and return to dialysis.

After your transplant, you’ll be followed up in the transplant clinic. Initially this will be 3 times a week for 4–6 weeks. The visits are gradually spaced out to twice weekly, once monthly and so on. When you have had your transplant for 3–4 years, you’ll only need to have 3 or 4 follow-up visits a year.

Ian had a kidney transplant in 2017

“The operation went smoothly and I woke in recovery as if nothing had happened apart from all the tubes. However, the following day I did feel nauseous, and was sick, then Day 2 started to go into full recovery, and Day 3 the kidney started working and all tubes were removed. On Day 5 I was able to come home.

Initially it went well. I have had a hiccup with a viral infection, but my lifestyle is getting back to normal. I'm feeling healthier, and about to start up physical fitness again. Even with the hurdles I’ve encountered, my GFR has been up to 65%, and I am looking forward to the future.”

Andy had complications after his joint kidney and liver transplant

“My operation was long and didn't go exactly to plan. I tried to stay pragmatic and positive about the recovery process which was not always easy or straightforward with infections, episodes of rejection and a 'sleeping' donor kidney.

Everyone's experience is different - I was in hospital for about 10 weeks. I had a few overnight visits over the next 6 months, but things settled down gradually. I celebrate the little victories (like having my first wee in 2 years!). For me, my 12-month anniversary was most significant both physically and emotionally - that was when I felt I had turned a corner in my recovery.”

Some patients experience problems after their kidney transplantation. These can include:

These problems can mean you need to stay in hospital for longer initially or return to hospital. Depending on the problem, you may need changes to your medications, additional medications and/or further surgery. You’ll be very well supported by your kidney and transplant team who will monitor your health closely and immediately address any kidney or other health problems you develop.

The survival of your transplanted kidney can be influenced by:

A kidney transplant can allow you to live many years. In the UK, 95 out of 100 people receiving a kidney from living kidney donor and 88 out of 100 people receiving kidney from a deceased donor, survive at least 5 years.

The length of time a person survives after their kidney transplant depends on a few factors. Survival tends to be longer in people who:

On average, overall survival is longer for people with a kidney transplant versus those receiving dialysis.

After having a kidney transplant, most patients find their quality of life significantly improves. The dietary restrictions that you needed to make beforehand (such as the amount of fluid you drank, and amount of potassium, phosphate and protein you ate) are no longer needed after a successful transplantation. The majority of people receiving a kidney transplant return to their normal lifestyles within a year. Patients can enjoy increased energy levels and participate in sports. If their ADPKD was affecting their fertility, this usually returns to normal.

Stephen has got more active since his transplant recovery

“I have no dialysis and no dietary restrictions and my fitness is such that I play golf, have been back pedalling on the bike and I competed at this year’s Transplant Games. Life will never entirely return to what it was before, but every day feels like a massive bonus. I am immeasurably grateful to the medics and of course to my donor and his family.”

Nicki’s quality of life improved, but there have been challenges too

“I have been on quite a journey over the last 13 years. Certainly, this donation prolonged my life span and increased my quality of life immensely - I have been able to travel, gain a Master's degree, continue to work for some time and create a home for myself.

I have also had to deal with the traumatic impact ADPKD has had on my emotional and physical health, and have had some unfortunate experiences of employers and colleagues not understanding what this has been like. Even so I wouldn't have had it any other way. To share life with another person is a great privilege in both directions.”

Rob found freedom from dialysis the biggest change

“Immediately after the transplant, my skin lost its yellow tinge and I gained a normal complexion. I felt normal again, just like I used to. The biggest change was no longer being tied to dialysis 3 times a week, and once again being able to do all the things that I used to without having to take regular breaks. One thing I will never forget. How lucky I have been.”

A kidney transplant will replace much of your lost kidney function, but it won’t cure your ADPKD. If your original kidneys aren’t removed before your transplant, they might continue to grow, which can cause pain, bleeding and infections. They can later be removed if needed in an operation called a nephrectomy. However, it seems that the original kidneys often shrink after a transplant operation, so you might not need to have them removed. It’s safer not to remove them unless they’re causing problems.

Having a kidney transplant doesn’t stop ADPKD affecting your liver, and liver cysts often continue to grow. If you have liver problems caused by your ADPKD, you’ll need to have these treated separately.

Although kidney transplantation is the best type of renal replacement therapy for ADPKD patients with kidney failure, not all patients are suitable and some may choose not to have the operation.

The alternatives to having a kidney transplant are:

Written by Mr Badri Man Shrestha, BSc MBBS MS MPhil MD FRCS(Eng & Gen) Hon.FRCS(Edin) FACS FICS FEBS, Consultant Transplant Surgeon, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

Edited by Hannah Bridges, PhD, independent medical writer, HB Health Comms Limited.

With thanks to all those affected by ADPKD who contributed to this publication.

IS Ref No: ADPKD.SP.2017V1.0

UNDER REVIEW

Disclaimer: This information is primarily for people in the UK. We have made every effort to ensure that the information we provide is correct and up to date. However, it is not a substitute for professional medical advice or a medical examination. We do not promote or recommend any treatment. We do not accept liability for any errors or omissions. Medical information, the law and government regulations change rapidly, so always consult your GP, pharmacist or other medical professional if you have any concerns or before starting any new treatment.

We welcome feedback on all our health information. If you would like to give feedback about this information, please email

If you don't have access to a printer and would like a printed version of this information sheet, or any other PKD Charity information, call the PKD Charity Helpline on 0300 111 1234 (weekdays, 9am-5pm) or email

The PKD Charity Helpline offers confidential support and information to anyone affected by PKD, including family, friends, carers, newly diagnosed or those who have lived with the condition for many years.